This exchange, and chart, illuminate the biggest challenge and biggest opportunity for Ed Miliband.

. @jamestplunkett But not feed through into consumer confidence on own finances yet. Big challenge. pic.twitter.com/rKOVK2NnyK

— Matthew Oakley (@MJ_Oakley) December 5, 2013

So, people expect the UK economy to be doing a bit better. They see an inflection point in February and then another one, marking a dramatic transition to growth, in June. Now the first thing that strikes me here is that I wonder what the same poll looks like for last year, as this might well be seasonality. But this is beside the point.

The other line on the chart represents their expectations of their own personal situation. This looks rather different, basically flatlining around -10% negative balance of opinion. There’s an uptick at the forecast horizon in August, but there was also one in August last year.

So, we have dramatically different expectations for the abstract concept of the UK economy, which is a national-level phenomenon primarily experienced through the mass media and mass politics, and for the lived experience of one’s own economic life, which is a local phenomenon experienced directly and through social contacts, local media, and perhaps also through the social media.

This phenomenon is a frequent observation in contemporary Britain. YouGov polls, for example, ask the questions “Which of the following do you think are the most important issues facing the country at this time?” and “Which of the following do you think are the most important issues facing you and your family?” Here’s an example (PDF). Immigration is no.2 in the first case, no.6 in the second. Europe is no.6 in the first, no.10 in the second. “Family life and childcare” is no.10 in the first, no.4 in the second.

I think of this as “political windshear” – the wind at ground level doesn’t blow with the same force or direction as it does at altitude. It doesn’t make much sense to talk about it in terms of voting intention, because after all there is no way in the Westminster system to express separate national and local preferences in a parliamentary election.

However, it is obvious that some of the best Tory (and Blairite) themes blow only at altitude, and that the big theme that cuts across all parties (the economy) is experienced very differently depending on whether we discuss the abstract notion of the economy or the personal and social experience of it.

On this basis, I see good reason for Labour to be optimistic – they are in a position to campaign on “Are you and your family better off now than you were in 2010?”, and have an opportunity to play a lot of successful conservative themes in reverse (e.g. the appeal to household finances, and rejection of abstract macro tropes in favour of stupid empiricism).

This is the inverse of the position in late Thatcherism, when although macroeconomic numbers and general mood-music were horrible, and a lot of people were in deep economic misery, a political majority existed that did actually feel better off.

If a recession is when your neighbour loses their job, and a depression is when you lose yours, a recovery is when George Osborne insults your intelligence on TV.

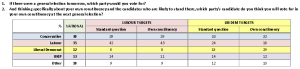

There is some reason to be cautious, though. I say that it doesn’t make sense to talk about national and personal voting intention, but there is a bit of data because Lord Ashcroft’s polling asks about it. This poll of 40 marginal seats, for example, asks both “If there were a general election tomorrow, which party would you vote for?” and “Thinking specifically about your own constituency and the candidates who are likely to stand there, which party’s candidate do you think you will vote for in your own constituency at the next general election?”

Table 2 summarises the results.

In Labour target seats, there is a very slight shear effect in favour of Labour and Lib Dem candidates (+1 and +2 respectively) and a bigger one against UKIP (-3). In Lib Dem target seats, there is a really strong shear effect in favour of the Lib Dem (+11) and against Labour (-6). It should be remembered that these are swings, so you can’t tot them up and claim a 17 point advantage for the Lib Dems versus Labour. The rest of this effect breaks down as the Tories losing 1 point, UKIP 2, Others 2 (i.e. 6+1+2+2=11).

Across the board, this implies that some substantial Lib Dem machine advantage still exists, but by its nature it’s concentrated in seats that are Lib Dem targets and that are LD-LAB marginals. It also suggests that in general, UKIP will do less well than national polls predict, by 2 to 3 points, although we would really need to see data about CON targets to understand this effect.

That said, the effect is relatively small in the context of a Labour lead of 14 in their 32 most marginal LAB-CON seats, and is generally much less significant with regard to constituencies than it is with regard to issues. If Labour get the message across that (to quote me) “voting may effect your interests. think carefully before voting”, winning the central CON-LAB contest would render Lib Dem survivors less interesting or relevant.

It also suggests that national parties, and especially Labour, should put more resources than they do into either taking local elections in targets ahead of the general election, or taking them afterwards in order to consolidate.

A successful shear campaign would probably tend to pull up national voting intention with it, but I haven’t attempted to model this.

Mike Smithson has also looked at this issue, and he argues that it means that Labour voters in LD-CON marginals are still likely to vote tactically, while UKIP voters are harder to win back for the Tories. This would be a net disadvantage for the Tories.

He also blogs polls of 2 high value CON-LAB marginals and finds a really drastic crash in the LD vote outside LD target seats.