What links all these items?

YouGov – 56% support rent controls. 33% against. Tories are going to have to come with a new attack line…

— roadto326 (@roadto326) May 4, 2014

No, its not a "lurch to the Left" : even 52% of Tory voters support renationalisation of rail and energy .. pic.twitter.com/ZEfDWMeNXX

— Labour Left (@LabourLeft) May 5, 2014

Why are Labour so reluctant to point to things which work in London – state-controlled trains, living wages, borrowing for infrastructure…

— MayorWatch (@MayorWatch) May 4, 2014

I’m going to focus on railway privatisation here because it’s the obvious bell wether; the last, most ambitious, most complex, and least popular of the privatisations, and the most marginal one, the one that unequivocally failed, that has been substantially rolled back but still won’t die.

It has been true, as long as there has been a privatised railway, that any British politician could do better in the polls by attacking it and by promising to reverse the privatisation. (It’s also true that as long as there was a nationalised railway, we whined about it, and indeed we whined about the railways ever since there’s been a railway.) There is even a simple policy option available to make it happen: stop issuing franchises and just let them all revert. Yet no-one with any power has been willing to take the step of making this option available on the ballot. The political system’s role as a mechanism for limiting the agenda has rarely been more clear.

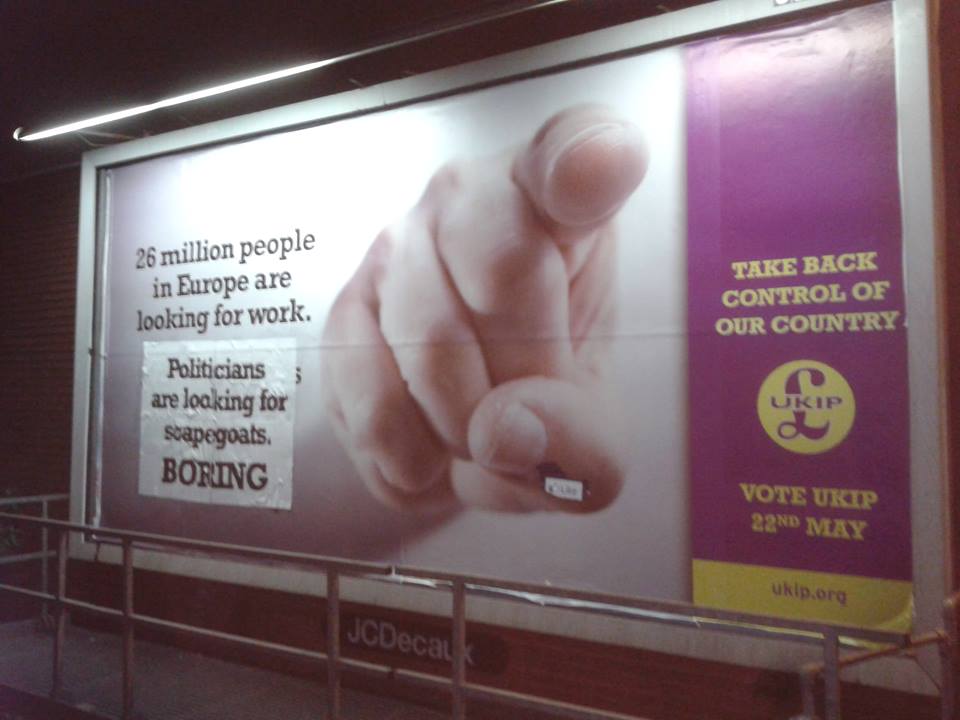

Even though the Department for Transport has progressively retaken control of much of the railway, and the infrastructure has been effectively renationalised, actually ending the private train operating companies would be what is termed an opting decision, one heavily laden with emotional content and that is thought to transform the decision-making entity (that’s us) itself. It would be to say that the choices of the 1980s are subject to the decisions of democracy, that in the UKIP billboard’s words, we have taken back control of our country.

(from Destroyed UKIP Billboards, and found in Leeds. Where else?)

This is, after all, why it was allowed to persist. Taking it off the agenda was a decision that set the limits of debate. Potentially powerful people were defined as those who believed nothing could be done; crazies as those who believed something could.

Politicians in Britain can broadly be divided into the ones who wish to shrink the offer, as they say, and maintain the principle that your basic interests – things like housing, wages, work, and infrastructure – are outside your or their control, and those who promise to return them to your control. It is no accident that the two most successful political projects of recent times, the current version of UKIP and the current version of the SNP, both speak to this.

Nobody believes for a moment, for example, that Pfizer won’t shut down the AstraZeneca R&D operation and transfer the patents home. They did it with all their other acquisitions. Nobody believes that any assurances given will be honoured. This Daily Hell story is intensely reminiscent of Iraq, the sheer range of people who have every right to be listened to queuing up to warn the prime minister, to the extent that you just know he’s going to do it anyway. And the best the Tories can offer is that Ed Miliband didn’t waste his valuable time listening to more worthless assurances.

Not so long ago, Rory Stewart MP was quoted as saying that nobody has any power.

In a way, he says, ordinary Afghans are far more powerful than British citizens, because at least they feel they can have a role in one of the country’s 20,000 villages. “But in our situation we’re all powerless. I mean, we pretend we’re run by people. We’re not run by anybody. The secret of modern Britain is there is no power anywhere.” Some commentators, he says, think we’re run by an oligarchy. “But we’re not. I mean, nobody can see power in Britain. The politicians think journalists have power. The journalists know they don’t have any. Then they think the bankers have power. The bankers know they don’t have any. None of them have any power.”

I think this is probably the most profound statement on British politics of the last ten or even twenty years. AVPS wonders why UKIP is so resilient to its own pratfalls. There’s your answer; we know that its voters don’t care much about the EU, and don’t agree with the policies the Kilroy-Silk era libertarians came up with. But they vote for them because they at least give the impression of control. It is of course no surprise that assorted “populisms” sprouted across the EU, an institution that explicitly promises to reduce national control over the economy.

This is also why efforts to dose left-wing politics with Euroscepticism have failed. It’s not, specifically, Europe that attracts people to UKIP, so you can’t simply install it like a software package.

Just like the quote, this is one of the best posts on British politics I’ve seen.

I’ve rambled on at Eurotrib about Learned Helplessness – as sort of the cultural end-game of post-Hayekian thought.

If you want a great example of how far it’s gone, take “Marxist Chris” from stumblingandmumbling – half of his posts are about how no-one can do anything. It’s the major frame of our thinking – yet all the time, the prevailing orthodoxy involves doing things, selling things to private concerns who then make out like bandits. Things are being done while it is pretended that no-one has any power…

I think it’s probably fair to say that there isn’t an elite pulling levers and controlling all our destinies, and that contemporary capitalism is heading further towards the law of the jungle. That said, it is still blatantly obvious that there are still people with enough wealth and privilege, or occupying certain positions in society, that they can at the very least manage to insulate themselves from the kind of problems faced by the majority. This group effectively benefits from the fact that the majority is unable to exercise control, but, strangely enough, this situation rarely comes into question and it’s foreigners and/or the poor that get the blame.

Permalink

Permalink

Permalink