So, ISIS. Through the open newslist it turned out that a lot of you could put off reading about Jimmy Savile until later if it meant hearing about the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria and why it seemed at the time to have the beating of the Kurds. Let’s begin with the geography, or rather, the mental geography.

Iraq’s a desert, see? All sand, camels, etc, except for the mountains, great towering snow-capped mountains. In the sand, camels, etc. you’ve got the Arabs who are either Good Guys with Moral Courage or else they’re Bad Guys who are our enemies in a generational struggle against their evil ideology, like Churchill an’ all.

That version didn’t work so well and we found out that some of the Good Guys like to drill holes in their prisoners and some of the Bad Guys are only Bad Guys because they’re scared of the worse element among the Good Guys, and if we could somehow reassure both the Good Guys and the better Bad Guys about this, the better Bad Guys might be able to tell us where the really bad Bad Guys are, and then we might be able to hand the whole Iraq problem to a joint Good Guy/OKish Bad Guy government and go home. That worked better. A bit.

While all this was going on, everyone except the worst of the Bad Guys agreed that the people in the mountains were the absolute best of the Good Guys, tough and scrappy guerrillas who actually practiced democracy and a version of religion less horrible than you might find in Texas, and whose institutions usually worked. Awesome. I refer of course to the Kurds.

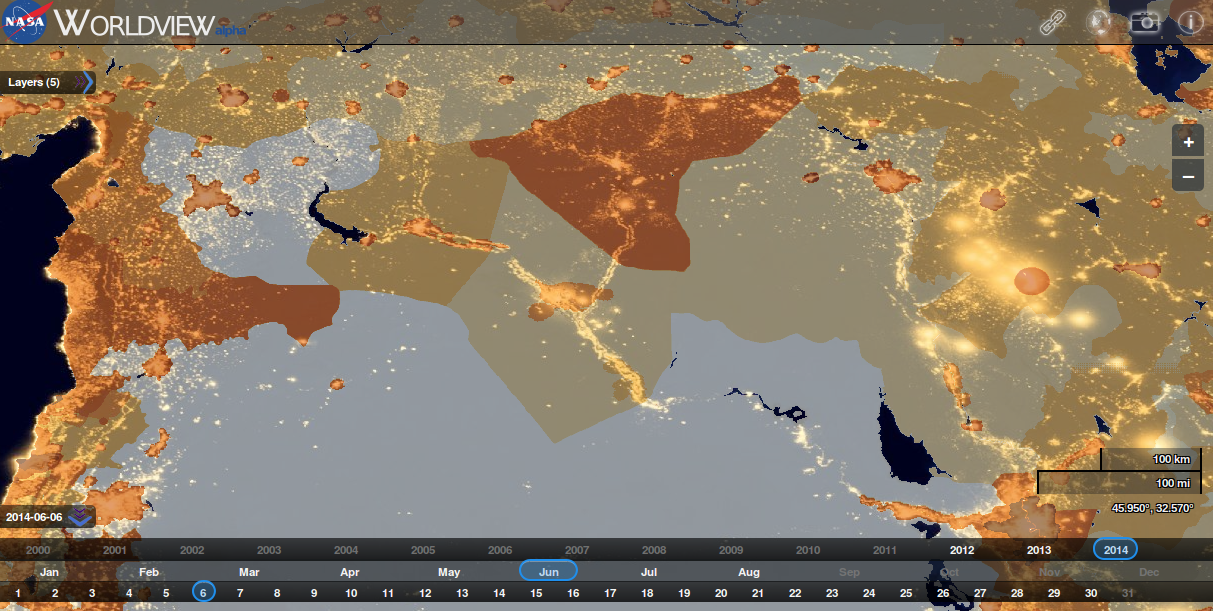

Now let’s look at some real geography. Here’s a map I made earlier with NASA’s fine Worldview web site, where you can see it in its natural habitat.

What we’re looking at is a standard basemap overlaid with temperature and population density information and night-time illumination, which is a finer-grained proxy for population in some ways but one that also reveals oil fields. Worldview lets you pick by date, so I’ve picked overhead imagery from the night of the 6th of June 2014. Yeah, 70 years to the day, but that’s not the point. The point is that it’s the night ISIS tore into Mosul. And I’ve centred the map over Deir ez-Zour, Syria, which might sound like either the middle of nowhere or else the middle of the world, or at least the Middle Eastern theatre of war.

First point. The people live near the water. Deir is nicely placed on the Euphrates valley, and if you don’t care about the border, from there you can easily campaign along the fine roads secular dictators built with oil money in either direction and you’ll find important things that matter, and possibly also friends. One way takes you to Aleppo and the other, Baghdad.

Second point. The people live near the water and also near the oil. Look how much population there is in Kurdistan and north of the Sinjar range – follow the river valley north from Deir and you’ll find it. Yes, I left the administrative borders off the map deliberately.

Third point. Per Wikipedia, which has a surprisingly detailed operational history in three parts here, here, and here, in the spring of 2014, ISIS was under pressure at both ends of the Euphrates strategic line of operations. Other Syrian rebels were attacking it around Aleppo and as far away as Deir ez-Zour, while the Iraqi government had by the 13th of April retaken Fallujah and the Fallujah Dam. The advantage of operating on interior lines is that you can dash from one front to the other faster than the enemy can; this falls down when the enemy coordinates. Ask a German.

Fourth point. A less scary group might have been beaten like this, but ISIS was equal to it. This situation demanded a strategic manoeuvre that would change the situation dramatically, and they produced one. The raid on Mosul collapsed the Iraqi command structure and opened up two whole new lines of operations, down the Tigris valley and into the populous north. Descriptions of the pursuit south in June concentrate on not so much fighting, but more a succession of what the Americans I mocked earlier would call key-leader engagements, with local security actors swapping sides to become ISIS franchises.

Fifth point. How did they do it? Again per Wikipedia, during March and April, they executed a retreat from Aleppo and the Turkish border to concentrate around Deir ez-Zour and secure their hold there. On the 6th of June, they attack Mosul from, per Wikipedia, the north-west, moving straight to the seat of government, the 2nd Infantry Division HQ, and the police HQ.

Hold it right there; look at the map. There’s a river road that leads a lot of the way there, from Deir towards Sinjar, Syrian Route 715. They didn’t, though, move along Iraqi Highway 7 through Sinjar and Tal Afar and then down 1 into Mosul from the NW, the obvious option, because they didn’t take Tal Afar until August. Even though the force that attacked Mosul has been estimated at 1500 strong, that’s still a column of 180 or so vehicles at 8 to a Toyota.

Perhaps they went…through the desert, like Bad Guys racing in on their horses to sabre the Good Guys as they sleep. Look at the map again. There are more people and more stuff NW of Mosul than you think. In fact, let’s zoom right in between Tal Afar and Mosul:

There are fields in this desert. Not oil fields, the other kind. Desert is obviously a very relative concept. In case you think I’m falling prey to “big hands, small maps, that’s the way to kill the chaps”, the land ISIS conquered over the summer produces 40 per cent of Iraq’s wheat. We probably shouldn’t think Rommel sweeping across the Sahara but rather, Mao swimming like a fish among the people. And this is what the north-west side of the city itself looks like. Turns out there’s a reason why there’s been a city there ever since there have been cities.

I don’t know about you but an intensive agricultural zone full of Sunni Arabs sounds a great place for ISIS to hide out the night before. OK, so. One of the big innovations of ISIS is just forgetting about the border, bringing the innovations of the Iraq War to Syria and vice versa. But it would be too strong to say that ISIS is just a brand. The movement from Deir to Mosul seems to have been very real, and it means they operate on a scale of 200 miles a bound.

Sixth point. ISIS structure and scale and strategy. Apparently it has seven regional commands, all with their own account on security-optimised Facebook analogue Diaspora:

PT: So far, the IS appears to be operating accounts on the Diaspora network for Raqqa, Janoub, Anbar, Diyala, Salah ad Din, Kirkuk & Aleppo.

— Charles Lister (@Charles_Lister) August 16, 2014

My mental model of this is that they have a core force which can be projected anywhere in that first map pretty quickly, moving fast on its wheels (usually Ford Rangers rather than the iconic Toyotas) and through its social context, plus a lot of semi-attached local sheikhs. This is weirdly similar to the original FRES concept – a fast, wheeled army that would intervene, change the political situation, and be gone leaving some other lot like the UN or the mafia to hold ground.

Seventh point. The Kurds. The super-good guys! In August, ISIS began a new offensive northwest from Mosul, having presumably recovered the core force from its rush on Baghdad in June. Having said what we’ve said so far, a big part of the point is probably to secure the road, Iraqi 7, that links their Tigris-Kurdistan-Diyala and Euphrates-Syria-Anbar fronts, as well as to deny the harvest to the Iraqi government and to spread pure terror. Another aim would be to deter the Kurds from interfering. It seems to be a standard ISIS move to go straight for leadership targets, see Mosul, and that would be why they threatened Irbil early on.

The initial Kurdish response to ISIS was to move forward and grab Kirkuk (that’s the really, really big blob of light on map 1). You can see why; it’s full of Kurds and oil. But the prestige attaching to this seems to have been a problem, causing the various Kurdish political parties to compete to get as many of their fighters into it as possible. Kurdish priorities also included Syria and their alliance-commitment to help out Maliki. This may not have left much.

Kurdish fighters in early August were often described as a reserve force (for example, here). Since then, per the still-essential Musings on Iraq, there has been a mobilisation across Kurdish parties in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, and a move towards a unified command, which might explain even more than US help why the situation has stabilised.

So, fighting ISIS effectively required abandoning the mental geography of the borders and adopting one based on reality. ISIS has framed its strategy on a scale given by the landscape, not by borders that are basically fictional at the moment. This might not be the most exciting story ever, but there you go.

[if your e-mail is “Adam Daniels” why is your twitter handle “Charles”?]

Permalink